Key Takeaways

- With rising concerns about AI wiping out jobs, both imagination warps and imagination gaps fail us in creating a new future where AI and humans work alongside each other instead of where AI destroys civilization.

- Salesforce Futures argues that we must use our imagination to create future scenarios that include both humans and AI agents working together to optimize business outcomes.

- Fostering this new workforce of humans and agents working together requires efforts in redesigning and rebalancing work as well as reskilling and redeploying employees for the digital labor era, while keeping an eye on the impacts of utilizing AI technology.

In May 2025, Anthropic founder and CEO Dario Amodei predicted AI could wipe out half of entry-level white collar jobs and spike unemployment by up to 20% over the next five years. In June, AI luminary Geoffrey Hinton warned that AI is different from previous technologies in its ability to replace all but the most specialized humans. Ford CEO Jim Farley recently suggested a halving of demand for white-collar work while pointing to a shortage in skilled tradespeople.

No one really knows if these warnings will prove correct. What we at Salesforce Futures know, from long experience, is that thinking productively about the future is fundamentally an act of human imagination. When it comes to AI and job displacement, however, this needed creativity is often distorted by an “imagination warp” and an “imagination gap.”

- The imagination warp is caused mainly by the powerful attractive force of dystopian narratives originating in sci-fi.

- The imagination gap refers to the lack of a shared framework for understanding how technology changed work in the past and that can guide our understanding of how innovations like AI could alter our lives, both positively and negatively, in the future.

The imagination warp: Existing narratives and AGI are failing us

Powerful dystopian sci-fi narratives provide easy, widely understood references for the media. However, they also reinforce the idea that bad outcomes are not only possible but also likely.

In movies like “Terminator” and “The Matrix,” machines use superior intelligence to rob humans of their agency. This dynamic is also common in the current AI doomer scenarios that focus on the possibility of “civilization destruction” or “AI apocalypse.” Ironically, even the more utopian-leaning Artificial general intelligence (AGI) predictions from Sam Altman warn that bad outcomes are likely if we don’t put checks and balances in place to control the technology. These powerful stories shape how every AI innovation, such as agents, is perceived. They’re all but a precursor to an AI that is so powerful and pervasive that it will make human workers obsolete.

AI isn’t the first automated technology to stir fears about job loss. From assembly lines that replaced skilled laborers in the early 20th century to ATMs that threatened bank tellers to automated switchboards that phased out operators, automation has a long history of making workers worry about their future. But in our futures work, as in life, we’ve found that negative scenarios are much easier to create than positive ones. They only require envisioning existing systems breaking down.

“All you have to do to develop a negative scenario is take reality as we know it and kick it to pieces,” writes futurist Jay Ogilvy. “Positive, optimistic scenarios, on the other hand, lack plausibility if they sound like a view of the future as seen through rose-tinted glasses.”

Closing the imagination gap: Toward a better framework for thinking clearly about AI and jobs

A balanced view of the future recognizes both the benefits and potential harms of restructuring work.

To be believable, positive scenarios must demonstrate how existing problems that are currently holding us back get solved. This is difficult: If solutions were apparent, they likely would’ve been implemented. Part of the challenge of futures work, therefore, is to develop a deeper understanding of how complex systems may transform and pair that knowledge with a willingness to imagine novel and unexpected solutions. If we can escape the narratives that limit our imagination, how may we more clearly think through the effect of AI on employment?

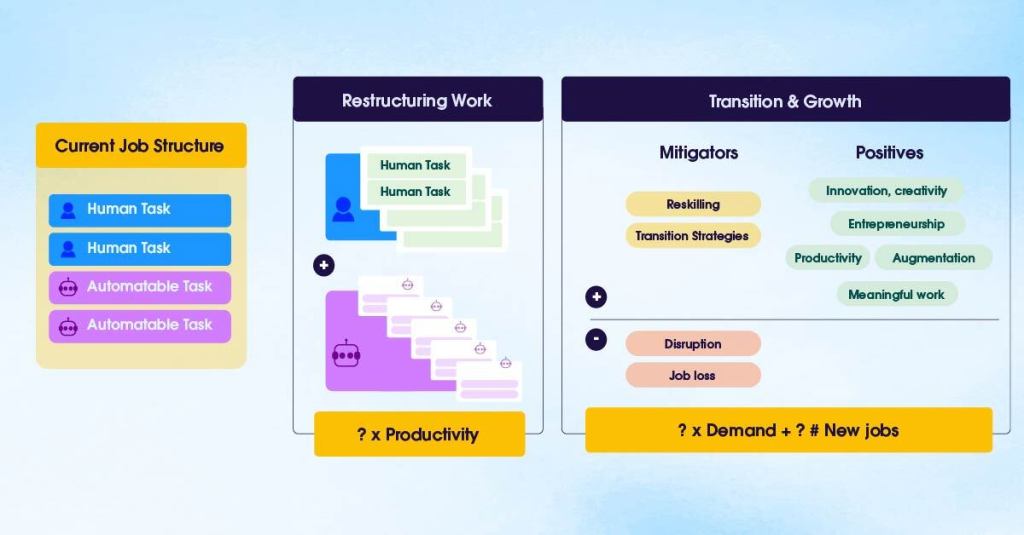

Understanding the future of work means shifting our focus from whole jobs to specific tasks — some of which can be automated, while many can’t.

Mick Costigan, VP of Salesforce Futures

Understanding the future of work means shifting our focus from whole jobs to specific tasks — some of which can be automated, while many can’t. The White House’s National AI Advisory Committee notes that economists’ views on which tasks are most likely to be automated have evolved, moving from a focus on manual work in the 2010s to today’s concerns about “intellectual and unregulated” tasks. The main questions: Which tasks will actually be automated? How will that reshape work? Which tasks will resist automation?

Even if AGI arrives sooner than expected and all tasks prove automatable, issues will remain to be solved as humans and AI work together. First, we need to accept that we’ll still face hallucinations and trust issues with AI. Second, we need to experiment and learn what AI is best at and what humans are best at. Finally, we should accept that even in circumstances where AI is proven to outperform people, there may be scenarios where we prefer humans and human-shaped processes.

In exploring how humans and agents will work together, we find inspiration in author Vaughn Tan’s focus on “meaningmaking.”

“What makes us human is our ability to do things which are not-yet-understood, which require us to be able to create meaning where there wasn’t meaning before,” writes Tan.

Framed this way, we can see how much meaningmaking happens in work — when we make tough, values-driven leadership decisions; make subjective judgments; or assess risk — and how central that work is to both personal and community identity. If we want real conversations about better AI futures, we must understand more deeply the nuances of work’s human side.

In a recent interview, Salesforce VP of Workforce Innovation Ruth Hickin emphasized that AI-powered work can also be “meaning-first” work.

“We have to design for meaning-first jobs. We don’t want to lose entry-level workers; as a society, we don’t want to end up with mass unemployment,” she said. “New jobs can become more interesting and complex because we can automate tasks that were previously given to people simply because it was their first job.”

Upsides to automating what can be automated

One consequence of the imagination gap is that we fail to recognize the immediate effects of automating the tasks that may be quite positive for net employment.

First, in many situations, the existing supply of offerings and services is labor-constrained beyond the demand that actually exists today. We experience this when a customer service call places us in a three-hour queue, relieved somewhat (but not really) by having a callback option. Using agents to solve for these kinds of supply gaps wouldn’t necessarily displace current jobs, and service levels would improve.

Salesforce Co-Chair and CEO Marc Benioff emphasizes the persistent need for human employment. “This is about humans and AI working together, not wholesale replacement of human beings,” he said. “Or if that opportunity exists, somebody needs to explain it to me, because, as the CEO of a 75,000-person company, I can’t figure it out.”

His perspective reflects broader economic realities: Tight labor markets are already pervasive today, and with declining birthrates and growing resistance to immigration, as MIT economist and labor expert David Autor suggests, “The industrialized world is awash in jobs, and it’s going to stay that way.” A new analysis from the Economic Innovation Group (EIG) adds weight to this conclusion, showing that occupations exposed to AI don’t exhibit elevated rates of unemployment, labor-force exit, or occupational switching.

Reinforcing this narrative are encouraging signals that AI may already be boosting productivity, as evidenced by recent labor market data showing a notable acceleration in output per hour growth. According to Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago analysis, productivity has surged and is now trending at more than 4% of baseline.1 If this trend accelerates due to broader adoption and improvement of AI tools, we should see a virtuous economic cycle where workers can produce more output per hour, enabling businesses to increase wages without raising prices while supporting noninflationary economic expansion and employment growth.

Another upside: Uncertainty relates to situations where demand is elastic to supply (i.e., as supply increases, demand will too). Again, history helps here. Economist William Jevons first predicted this paradox with demand for coal in the 19th century. More recently, the arrival of spreadsheets on PCs presaged an explosion in demand for the kind of quantitative analysis they enabled.

Today, AI tools are already showing results in increasing developer productivity. An early controlled experiment by Microsoft Research and GitHub found that developers using GitHub Copilot completed programming tasks 55.8% faster than those without AI assistance.2 While a 2025 METR study found more mixed results for experienced developers on complex tasks, the broader trend suggests AI can open up coding jobs to a far broader swath of people by eliminating technical barriers, a point long made by AI pioneer Andrew Ng. The early, post-ChatGPT predictions by Ng and others seem to be bearing out, as new agentic coding tools increase the likelihood nondevelopers can create functional software applications. Venture capitalists Paul Kedrosky and Eric Norlin believe this could reveal a much higher level of true demand and even solve for what they call “society’s technical debt,” the backlog of useful applications that were never built due to developer scarcity rather than lack of need.

Reskilling and transition strategies

Where jobs are being displaced, recent economic history offers some caution. In the context of late-20th-century deindustrialization, the promises of reskilling factory workers for the knowledge economy too often fell short, leading to not only the loss of millions of jobs but also persistent long-term unemployment in postindustrial areas. Beyond the exaggerated narratives of science fiction and AGI, it’s these experiences that weigh heaviest on the minds of workers and policymakers alike. Thankfully, multiple reasons exist to expect more from the AI revolution.

First, the gap between the skills required for the knowledge jobs of today and the knowledge work of the future is smaller than it was in the transition from the manual, semiskilled roles that were lost to industrial automation.

Second, AI promises us much better tools. We’re increasingly capable of mapping the skills workers have today, understanding what skills they may need in the future, and plotting a personalized path from here to there. AI-powered coaching tools will also personalize learning and prove more accessible to the people who use them than past learning systems. In particular, we see enormous promise in newly-cost-effective, data-rich simulations that allow mutual testing of aptitudes and interests for emerging roles. For example, you practice for a job interview as many times as you need to before the actual event, rehearse for big meetings with much greater fidelity than today, or even run launch simulations of new ideas to refine go-to-market strategies before an expensive pilot phase.

Entrepreneurship and innovation

If past waves of innovation are a guide, AI agents may lead to a surge in entrepreneurial activity. The same AI-powered coaching and tools that help people reskill could also help people find and prepare for new entrepreneurial opportunities and provide cheaper access to expertise. This could fuel an entrepreneurial surge where people with great ideas could hone and deliver them without as much resource overhead.

We believe that a rising tide of accessibility — abundant intelligence, expertise, and support — will make it easier than ever before to start and run a business. Already, we’re seeing freelancers with unfettered access to resources, such as financial and legal expertise, that until recently would have been reserved for large companies. This also extends to more creative aspects of work. At last year’s Dreamforce, Cristóbal Valenzuela, CEO of the AI video creation company Runway, pointed out how technological constraints have historically held back people who may want to tell stories but lack the skills.

We’ll also see the arrival of entirely new jobs. A study led by David Autor quantified that 60% of the jobs Americans held in 2018 didn’t exist in 1940, as new technologies created the need for new roles.3 AI looks to follow the same pattern. Imagine agent builders and trainers, interpretability experts who audit decisions (and the models that produce them), and other new roles enabled by the change AI creates.

In the first issue of Salesforce Futures magazine, focused on personal AI agents, we imagined scenarios where agents mediate the majority of interactions between customers and companies. In a world where this kind of automation is abundant, the value of high-quality, human-to-human interactions should rise, especially for more novel circumstances where human attention is needed to help customers solve difficult problems and navigate decisions. These human moments will be one of the most important ways for companies to build trust with their customers and differentiate themselves from competitors. It stands to reason these companies will invest more in roles focused on personal service, conflict resolution, and relationship building.

Actions and conversation

We believe AI can be designed and built in a way that benefits us all, and Salesforce’s recent actions demonstrate this commitment in practice. The recently launched Workforce Innovation Playbook is built around the “4Rs”: Redesign how work gets done, reskill employees for the digital labor era, redeploy talent to unlock agility, and rebalance work to focus on high-impact activities.

As Salesforce’s President and Chief People Office, Nathalie Scardino, explains, “Everything we thought about how organizations operate is now antiquated as we design for human and agents working together. … Agents are not about replacing people, they are about releasing us from the routine, the bureaucracy, the noise — and augmenting human productivity, creativity, and purpose.”

The 4R framework reflects a broader philosophy of keeping humans at the center of the AI revolution. Salesforce’s investments in AI literacy through Trailhead, Agentblazer certification programs, and initiatives like Career Connect — an AI-powered internal talent marketplace — are all concrete steps toward ensuring that AI benefits workers rather than just displacing them.

Multi-stakeholder efforts to anticipate and protect against harm and to maximize opportunities remain essential. Salesforce participates in the U.S. National AI Advisory Committee, National Institute of Standards and Technology, and Singapore’s Advisory Council on the Ethical Use of AI and Data, for example. Governments have an important role to play in designing programs that broaden access to new technologies, from ASU’s $34.6 million digital equity initiative to the responsible AI partnership between the Block Center at Carnegie Mellon and the state of Pennsylvania, to the EU’s Digital Skills and Jobs Platform supporting digital upskilling across Europe, to Singapore’s national AI strategy.

As Salesforce and other tech companies deploy agents at scale, we have a responsibility to pay attention to the impact this new technology has on humans, workforces, and communities. We’ll not only learn what agents are capable of and how humans and agents best collaborate but also learn about agents’ limitations. Widespread adoption of agents will reveal unintended consequences, second-order effects, and surprising use cases we might not have even imagined.

As Salesforce and other tech companies deploy agents at scale, we have a responsibility to pay attention to the impact this new technology has on humans, workforces, and communities.

Mick Costigan, VP of Salesforce Futures

Active engagement matters more than ever. As Marc Benioff warns, “If we accept the idea that AI will take our place, we begin to write ourselves out of the future — passengers in a rocket we no longer steer. But if we choose to guide and partner with it, then we can unlock a new era of human potential.” Businesses must learn rapidly and share their insights far and wide so that all stakeholders — policymakers and educational institutions included — can make better decisions about workforce impact.

We know AI will set off yet another wave of creative destruction. We don’t know how exactly this wave will crash or where the balance will fall between jobs created and lost, but the lessons of the past suggest we may well be surprised on the upside. With clearer thinking and more engagement, we can move beyond both pessimistic proclamations and techno-optimistic boosterism, rebalance the conversation, and recover our agency. This is the best way to a future of AI and humans working together.

More information:

- Read more insights from the Salesforce Futures team

- Read more on how Agentforce is inventing the future of agents

- Learn more about personal AI agents

- Peek into the future of AI-human collaboration at work

1 Goolsbee, Austan. “Remarks on Productivity Growth and Monetary Policy.” Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago, 28 Feb. 2025, www.chicagofed.org/publications/speeches/2025/feb-28-siepr-economic-summit.

2 Peng, Sida, et al. “The Impact of AI on Developer Productivity: Evidence from GitHub Copilot.” arXiv preprint arXiv:2302.06590, 13 Feb. 2023, https://arxiv.org/abs/2302.06590.

3 Autor, David, et al. “New Frontiers: The Origins and Content of New Work, 1940–2018.” The Quarterly Journal of Economics, vol. 139, no. 3, 2024, pp. 1399-1465, https://doi.org/10.1093/qje/qjae008.